I think a fair few of will know that Harris have been a big part of my life. It’s 40 years since first seeing a Harris on the cover of Superbike magazine and 36 years since collecting my first frame kit from the Hertford factory in December 1987.

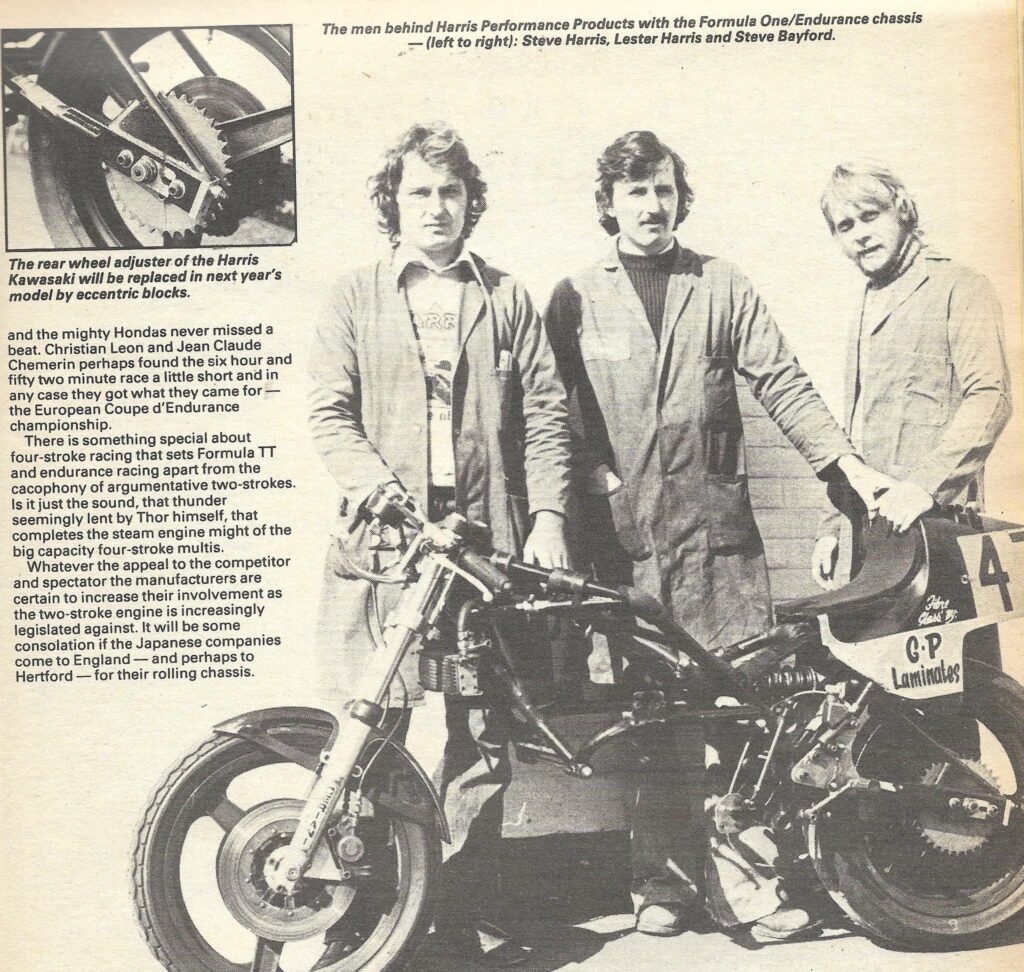

Harris performance products have been building bikes in various forms since the early 70s. Brothers Lester and Steve Harris formed the company together with a third director Steve Bayford. As I settle down to watch the British F1 grand prix from Silverstone I read on facebook that Steve Bayford has resigned, effectively ending the era the three created when forming the Company. Steve Harris unfortunately passed away in 2022 after a long fight with Parkinsons. Steve retired a few years ago due to ill health and never had the opportunity of enjoying the fruits of his labours. Lester retired soon after and is now enjoying his retirement.

I message Lester to lament the end of an era and ask him if he might consider having a chat with a view to me writing an article for itsonlyahill. Lester replies a short time after saying he would be happy to.

This article is the result of sitting down and listening to someone who has been involved with motorbikes and racing all of his working life, and he is still racing, supporting son Cameron. We meet at a pub close to his Hertfordshire home, I know from previous conversations with Lester there will be no shortage of things to talk about, questions to ask and stories to be told.

I first really met Lester when I dropped off my Magnum 1 at the factory to have a rear astralite wheel fitted, returning at the end of the working day the bike had not moved. I had been expecting to collect, pay and ride home, in the end I did, as Lester stayed late and fitted the wheel, aligning, making the spacers and rear brake caliper plate. As the job drew to its conclusion Lester tightened the rear axle nut with an adjustable spanner, that’ll do me I thought, if Lester can use an adjustable, so can I.

I have always valued being able to speak to the people who designed and built the bike I wanted to ride. I’ve been a desk jockey all my life, I’m no engineer, both Lester and Steve always seemed to get that and took the time to explain the mechanics of whatever it was in a way that I understood, I have always appreciated that.

We start chatting. The Enfield connection came about after Watsonian Squire who were the Enfield importers between 1999 and 2013 asked Harris for assistance with the development of a twin leading shoe front brake. Enfield had also commissioned another British firm Xenophya design, based in Northumberland to work on the design and development of the Continental GT a bike for the British and wider market. Mark Wells of Xenophya contacted Harris to assist with the engineering aspects of the project. Enfield bought both companies, buying in the expertise so they could develop their products quickly. Enfield also built the Royal Enfield Technology Centre at Bruntingthorpe, Lutterworth in 2017, it is now their global headquarters for product strategy, development, industrial design, research and programme management.

Harris now start trading as Harris Performance (a unit of Eicher Motors Ltd), they remain based in Hertford, resisting attempts to get them to move to Bruntingthorpe. Lester has worked closely with the factories in India which are modern and highly mechanised. Harris are a company use to creating one off projects and parts, Enfield are looking at mass production, combining the two mantras has been interesting. It could be argued that this is what has secured Harris into the future as the company could so easily reduced in size as the owners and workforce got older, potentially disappearing with no one left the steer the ship. Harris will continue to operate as a stand alone business, supporting the frame kit side of the business whilst developing kit parts for current and future Enfields.

Harris has kept its identity, a small unit of 15 or so staff developing products, racing and supporting the road aspects of the business, all now within a large conglomerate employing thousands of people who’s mantra is to develop the mass production of motorcycles to a worldwide market. From the beginning the Harris philosophy has been the company can only be as good as its staff, and the staff at Harris have been the bedrock of the organization. Many with over twenty and even thirty years’ service. Lester pays tribute to the quality of the people they have worked with over the years, emphasising to me they could not have achieved what they did without the hard work of the team that made up Harris Performance Products over the years. With Steve, Steve and Lester gone, Nick Daish is the only original member of staff still working in the factory.

Lester believes they were very lucky, to be in the right place at the right time, the early 70s promoted a “can do” environment, they did just that. Harris came from no plan, no idea as far as business but plenty of project ideas and engineering solutions, flourishing over the years, running teams in many classes of racing including privateer 500 Grand Prix (GP) and factory World Superbikes, (WSB). All stemming from a small company with good ideas and an ability to develop them.

The Lee valley around Hertford was full of engineering companies with a big pool of talented engineers supporting various forms of racing. Lotus were based in Cheshunt, Zipkart, Racing frames in Ware, who Steve worked for as a welder and Cameron Engineering who Lester worked for as a fitter and turner. Lester and Steve were involved in racing from early in their working careers, developing their own bikes and making parts, this soon snowballed and led to the creation of Harris Performance Products, staffed by clever people who like building and learning together, often working late and weekends to ridiculous, self-imposed deadlines, Lester doubts that could or would happen now.

The three directors each found their niche within the firm Lester and Steve designing and engineering with Steve often overseeing racing, Lester the road frame kits and Steve Bayford focusing on business aspects and the general running of the show.

The Japanese invasion of bikes was coming and the early bikes as we know didn’t handle. Lester tells me they found it very easy to make improvements. The wrap round frame coming from their early ventures into endurance racing with Mike Trimby and Andy Goldsmith campaigning a Harris framed Z900. Initially they ran a more conventional style spine framed bike with a bolt on subframe but access to the engine and carbs was restricted. The wrap round frame design they created gave full access to the top end of the engine and carbs which continually caused issues, lifting the tank exposed all the inner workings allowing removal/replacement/servicing of parts as needed.

The involvement in racing leads to the creation of their road going frame kits, the Magnum range. Initially they were built out of Reynolds 531 steel, glued together by bronze welding, more forgiving than TIG welding.

Later frames were T45 and later still Cold Drawn Seamless steel, as Reynolds became unavailable and really, for road going bikes not that crucial, were weight was not as important as in the race arena. I ask Lester why Magnum, he ponders, not sure where the name comes from, something catchy, macho, maybe it came from the Clint Eastwood films. They did try changing the name of what we know as the Magnum 3 to the M3R, but everyone called it a 3!

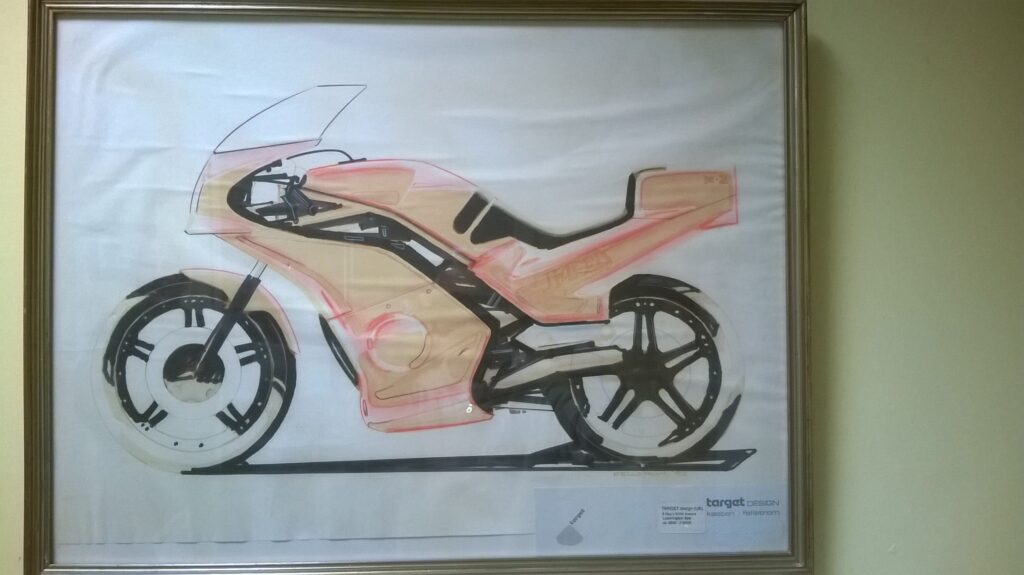

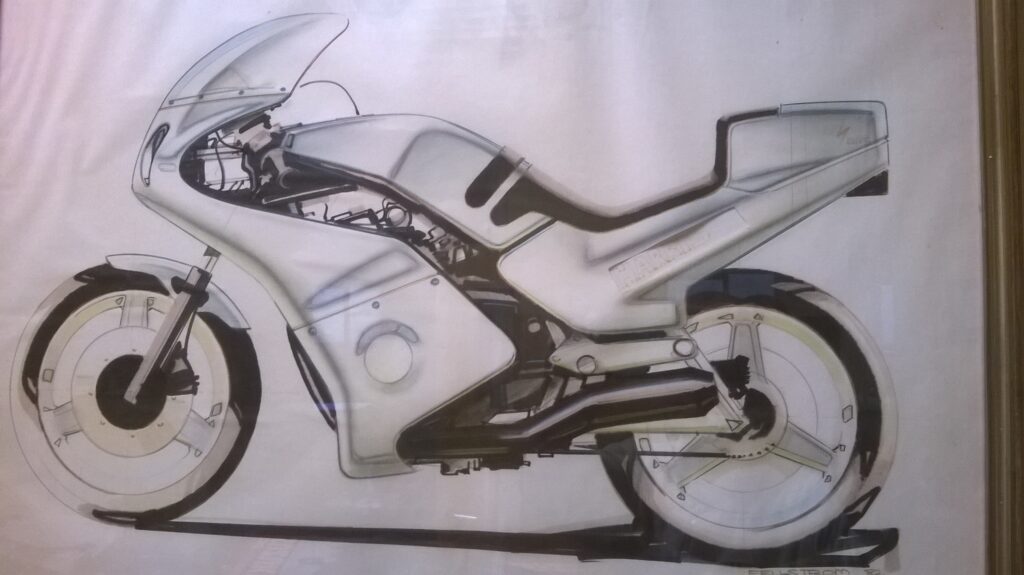

By their own admission the styling of the Magnum 1 didn’t appeal to all. Steve, the more outgoing brother phones Target design, based in Germany who have just designed the Suzuki Katana and asks them to design for them, they agree and the Magnum 2 is born. For clarity I ask the question so often posed, the difference between the 1 and 2 frames, “no difference” replies Lester, “it’s the bodywork, frames differ based on the customer orders, a bracket here or there depending on bodywork and such like. Early frames did have a higher rear bottom engine mount, this was lowered on later frames to help chain run.”. The cantilever rear suspension and positioning of the engine can cause some chain run issues with the tight spot of the chain coming mid suspension travel.

The 1 and 2 were the combined effort of the brothers, later models would see one of the two taking the lead, the Magnum 4 is Lesters’, the F1, Steves’, but whichever had the lead the other wasn’t far away, always on hand. I ask Lester how he feels when he sees one of their frames being cut around and altered, I’m surprised that he answers he’s ok with it, people are doing their own thing, something Harris advocate and have done all through their working life, he doesn’t like bodges though, they don’t look pretty and in some cases are just downright dangerous.

Racing improves the breed, the Harris mantra, that’s where the business started and the company has been involved in racing throughout. They’ve worked with lots of riders over the years, to name a few, Whitham, Emmett, Reynolds, Foggy, Rutter, Hislop, Sheene, Mike Trimby, the list is much longer but these were the names mentioned in passing.

Mike Trimby later founded International Racing Teams Association (IRTA) representing riders and teams in racing since the 80s. Trimby is a can do person, he has organized entries for Macau for years and on one occasion chartering his own jumbo jet to take people to Daytona.

In 1991 Yamaha supplied factory 500 engines to Harris and French firm ROC. The Harris link came from Steve’s friendship with Kenny Roberts. Kenny, apparently was unhappy with the Yamaha factory input and was looking to have frames built with factory supplied engines, Kenny’s involvement in the project ended but Yamaha like the idea, suppling engines with as much or as little help as teams wanted. The GP grid at that time was only a handful of bikes, numbers could be increased by allowing firms access to factory engines to run teams and sell bikes to other interested parties.

The initial Harris bike mimicked the Rainey bike of previous years, but soon they were changing things, developing different chassis configurations. Harris had other involvement in the GP world with Barry Sheene, Sheene came to Harris in the early days wanting to work with them, asking them to make alterations Suzuki wouldn’t, to his specification, one of which was a rear suspension set up with rockers at top and bottom. Unusually for a known rider Sheene was happy to pay for their services, rather than like some who wanted their services for free. Post race Barry would always phone the brothers up to tell them how the meeting had gone, as Lester recalls, this is in the days of expensive international calls, Barry also went out of his way to promote the company, something Lester tells me they always appreciated, top bloke!

The involvement with Yamaha gave the firm a leg up and a higher profile. Steve’s friendship with Suzuki race manager, Gary Taylor led to them campaigning the GSXR750 WT in WSB in 96, 97 and 98, Lester ran the team. Both Reynolds and Whit rode for the team. Whit was a firm favourite to work with, always giving 100%, other racers might have been more focused but everyone like working with Whit. He also rode the YZR500 at Macau under Steve’s wing.

Lester fronted the WSB effort and rates John Reynolds highly, naturally Suzuki wanted to win the WSB title, but, it turns out, the bike just wasn’t good enough. On receiving the bike the team conducted tests at WSB circuits where lap times were known, Reynolds was on the pace. The team went to Daytona and Reynolds went out on race tyres for the first time, the bike developed a wobble at speed, (Reynolds refers to it in his book as a death weave, stating he never made friends with the bike) he couldn’t get within 20 seconds of the lap record. The stability issues didn’t affect team mate Kirk McCarthy. The team altered everything in an effort to eliminate the issues but never bottomed it. Daytona that year didn’t happen, a hurricane blew in cancelling the race.

The stability issues continued to plague Reynolds, at Hockenheim Troy Corser asked Lester what was going on with Reynolds bike, it was all over the place, Lester and a Suzuki factory rep walk over to the long straight to watch, Lester tells me Reynolds passed them circa 185mph with the bike going lock to lock, frightening, Reynolds never complained, too much, and never refused to ride the bike, hell of a rider. The factory rep withdrew the bike from the race.

When I mention the TT Lester’s expression changes distinctly, I almost regret asking the question. “We have been, I’ve been, I was at the TT, with a rider, he was riding other bikes as well as ours, he went out for a lap on the Britten with the intention of coming in to take our bike out for a lap, and he didn’t come back, I pretty much phoned the factory up and said this isn’t for me”. I leave it there and move on.

Harris also worked with Shell oils as part of their scholarship programme, John McGuiness and Sean Emmett amongst the riders. Emmett went on to race a YZR in GPs taking the shell funding with him. Emmett also worked for Fast Bikes magazine, the editor Colin Schiller knew how to spot a good rider. He told Harris they should look at Shakey Byrne. By now Harris involvement in WSB had come to an end. They took on Shakey for British Superbikes (BSB) riding a Kawasaki, they entered him in the privateer cup as they were not a factory team, he finished 6th or 7th in the first race causing an uproar in the paddock, the other teams were not happy with his pace, insisting it was a factory team, Harris had to change his future entries.

I ask what his favourite bike is/was, perhaps surprisingly it’s a project they never really got to finish, It’s the Sauber Petronas Moto GP bike. They built the chassis to house the 4 stroke engine which would be taking over from the 2 strokes in 2002. The project, as ever ran on a tight deadline, from concept to working bike in about 14 weeks, with the intention to demonstrate the bike at the last 500 GP of the year in Malaysia in October. Sauber Petronas changed their mind about competing in Moto GP, they now wanted to compete in WSB the next year. With only a few short months to design, produce, test and do everything else that was needed, like build 200 bikes for homologation Harris pulled the plug, it couldn’t be done in the timeframe required, this was a 2 year project at least. The consortium led by Carl Fogarty stepped forward, strangely it took them 2 years to get somewhere near producing a bike, most of which have never seen the light of day, that story is documented elsewhere.

In retirement Lester looks after son Cameron’s bike, that’s keeping him busy most of the time, when not spannering Lester is still riding bikes. Trips over recent years have included Peru, Morrocco, USA (on Harleys, great trips, not so the bikes) Spain and Portugal, Lester likes a destination trip rather than just popping out for a quick spin, besides the roads round where he lives are just too crowded. In the garage sits a BMW 800, no Harris, to his regret. A few years ago someone offered the company the first road going frame, wanting an extortionate amount of money, the offer was declined, but Lester smiles ruefully, should have bought it. The same tale surrounds one of Lester’s early race bikes, a T500, offered to him in bits, in the back of a pick up, all rust and corrosion.

A big thank you to Lester for his time and providing me with more of an insight into the company two brothers and a school friend created out of a love of motorbikes and racing.

Harris, when only the best will do!